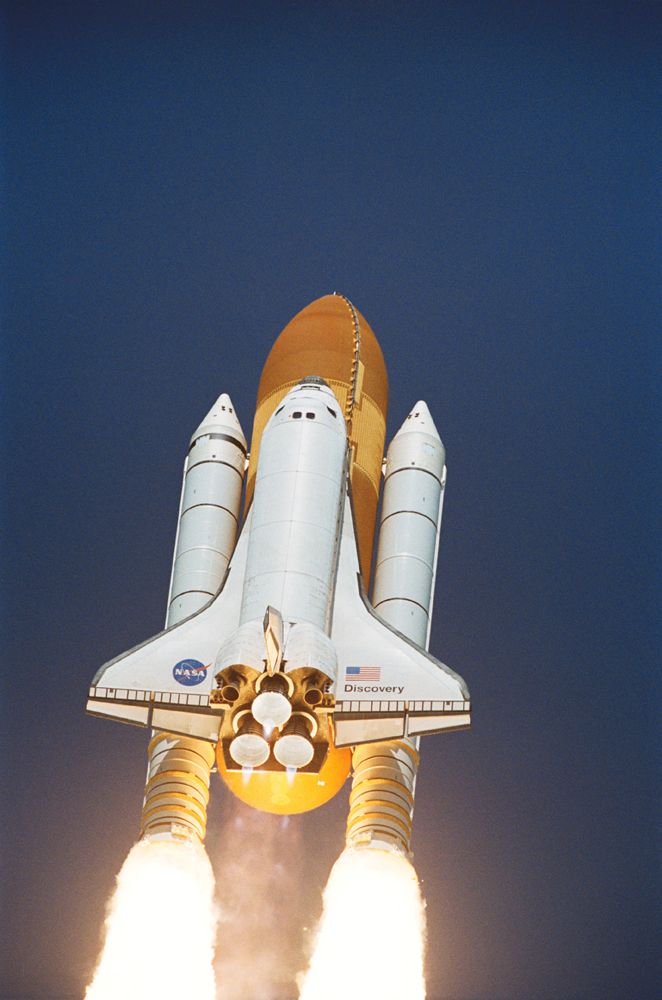

It was similar to the second stage of Apollo’s Saturn V-a bit smaller in diameter but longer and using similar materials and welding techniques. The number was arrived at by doing the math on how many flights would be needed to meet the financial goals of low pre-launch cost.įrom a technical point of view, the structure of the external tank was not especially complicated. We knew, too, that the proposed sixty shuttle flights a year in the revised plan were probably not realistic. The April 12 launch at Pad 39A of STS-1, just seconds past 7:00 a.m., carries astronauts John Young and Robert Crippen into an Earth orbital mission scheduled to last for fifty-four hours, ending with an unpowered landing at Edwards Air Force Base in California. As a rule, those investments pay off, but political and economic realities often stand in the way of making them. In almost any space program, the bigger investment you can make up front, the lower the operating costs will be. Our initially more expensive design would have been more economical in the long run. It was essentially the design that was eventually built: recoverable solid rocket boosters and a disposable external fuel tank that supplied the propellants to the orbiter’s three main engines. We came back quickly with a new $5 billion configuration and program. We were disappointed, but we had to find a way to live with that budget constraint. The problem was that design and development of that configuration would cost about $10 billion and Congress was only willing to authorize half as much. The proposed engines would have had enough power to circularize the shuttle’s orbit but not enough to do the heavy lifting to reach orbital velocity. Our first proposed booster–orbiter configuration featured a flyback booster and smaller engines on the orbiter than those in the final design.

The frequent budget discussions were held at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C.

That meant multicenter working groups meeting and communicating frequently, lots of travel, many meetings at Johnson with management and technical people, and daily communication at the program and project level. For instance, avionics and flight control systems were on the orbiter but directly affected the control of the main engines and solid rocket boosters, so success depended on a tremendous amount of coordination and integration. Although centers and contractors had primary responsibility for different elements of the shuttle system, those elements were tightly interrelated. The program office was at Johnson Space Center the engines, solid rockets, and tanks were developed at Marshall and ground operations were at Kennedy, with major work done by contractors North American Aviation, Lockheed Martin, Morton Thiokol, and Rocketdyne, among others. Work on the shuttle program was widely distributed. I was the project manager for the Space Shuttle external tank for eleven years, from the planning days in 1971 through the launch of the sixth shuttle flight in 1983.

The shuttle program was NASA astronauts’ ticket to space for 30 years. President Nixon’s announcement last week of the decision to begin development of a space shuttle system may prove to be nearly as crucial to the future of the manned space program as the 1961 Kennedy challenge to land a man on the moon. The decision on the shuttle is ‘go’ - Science News , January 15, 1972

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)